Trompe l’oeil: A Journey Through Illusion and Anamorphic art

The history of trompe l’oeil painting is a fascinating journey through the story of art. It spans millennia and encompasses many civilizations. This mesmeric art form, which translates to “deceive the eye” in French, is celebrated for its ability to trick viewers into believing they are seeing three-dimensional objects on a two-dimensional surface.

Here we explore the evolution of trompe l’oeil painting across different epochs.

Ancient Greece and Rome (5th Century BCE – 5th Century CE)

The origins of trompe l’oeil can be traced back to ancient Greece and Rome. Many ancient Greek artists were renowned for their mastery of illusion. The best known are Zeuxis and Parrhasius. There is a traditional story that Zeuxis painted some grapes so realistically that birds that entered the room attempted to eat them. Parrhasius went a step further when he painted a curtain so lifelike that even Zeuxis was fooled and tried to draw it back.

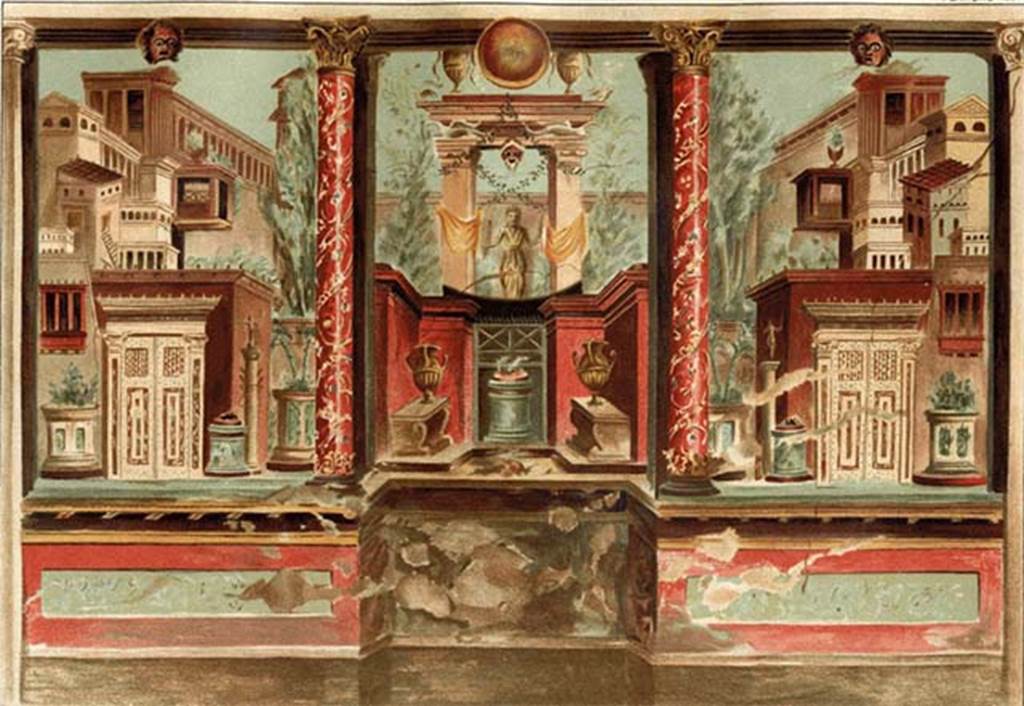

During the Roman period, the art of trompe l’oeil reached remarkable heights. Wonderful examples have been preserved in the excavated cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. These were buried in 79 CE by an enormous eruption of Mount Vesuvius and lay undiscovered for centuries under layers of volcanic ash.

In Pompeii, a once thriving Roman city, trompe l’oeil was used extensively in the decoration of domestic spaces. One of the most famous examples is in the “Cubiculum of Boscoreale.” This is a bedroom adorned with frescoes that give the illusion of luxurious architectural elements. These paintings contain faux architectural features, such as columns, pediments, and alcoves which made the room feel more opulent and spacious than it really was.

In Herculaneum, another Roman town similarly preserved by the volcanic eruption, the Villa of the Papyri displays exquisite examples of trompe l’oeil in the form of intricate mosaics. This illusionary artwork served as a testament to the wealth and high taste of the villa’s owner.

These ancient Roman examples of trompe l’oeil demonstrate not only the technical skill of the ancient artists but also the owner’s desire to live in beautiful and visually compelling environments in their homes.

Renaissance (14th – 17th Century) ‘Quadratura’

During the Renaissance, trompe l’oeil techniques were revived and refined by some of the most celebrated artists in history. At this time the technique was termed “quadratura”. It was a remarkable and transformative technique that allowed artists to create the illusion of infinite space on two-dimensional surfaces. The technique, deeply rooted in mathematics, architecture, and artistic skill, played a pivotal role in the development of monumental mural art.

The earliest record from this period was the story of the Florentine painter Giotto (1267-1337). It in Vasari’s celebrated book: Lives of the Artists (1550). Giotto, in deciding to play a trick on his tutor Cimabue (1240-1302) painted a tiny fly on the mural upon which the maestro was working. Cimabue then went crazy trying to brush away the fly, before he realized it was an illusion.

During this period with increased understanding of perspective and 3-dimensionality in painting developed. Use of quadratura is to be found in many thousands of frescoes and murals of the period throughout Italy. Famous examples include Andrea Mantegna’s “Camera degli Sposi” in the Ducal Palace of Mantua. It is often cited as a leading example of what was known as di sotto in sù (“from below up” in Italian). The ceiling is a trompe l’oeil ‘oculus’ that creates the illusion of a dome seemingly open to the sky.

The Baroque era witnessed the evolution of quadratura into a more dramatic and emotionally charged form of illusion. Artists of this period, like Giovanni Battista Gaulli (Baciccio), Andrea Pozzo, and Raphael, pushed the boundaries of perspective and space manipulation.

Baciccio, for instance, is renowned for his work in the Church of the Gesù in Rome. The swirling, heavenly figures in his ceiling fresco and the convincingly receding architecture create an overwhelming sense of awe.

Andrea Pozzo, in the Church of Sant’Ignazio in Rome, used it to create an astonishing illusion of a dome where none exists in reality. The ceiling appears to open up to the heavens.

Raphael, famous for his mastery of perspective, incorporated trompe l’oeil into his frescoes. In the Vatican’s “Stanza della Segnatura,” he painted the celebrated “School of Athens,” where the illusion of a grand coffered ceiling and architectural features were masterfully rendered, the great philosophers framed in architectural splendor.

Giulio Romano, a pupil of Raphael, left an indelible mark on trompe l’oeil art with his work in the Palazzo del Té in Mantua. One of the most famous rooms in the palace is the “Room of the Giants,” where the ceiling and walls appear to be caving in, as huge giants demolish the painted columns holding up the ceiling. This audacious illusion is a testament to Romano’s artistic skill and fecund imagination.

17th & 18th Century Rococo

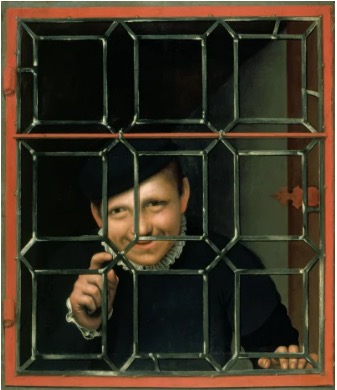

Trompe l’oeil indeed reached its zenith during the 17th & 18th centuries. Dutch artists, in particular, were masters of this captivating technique. Beyond portraiture and still life, artists of this era found ingenious ways to fool and amaze viewers with their remarkable paintings. Here are a few more examples of what has been achieved with trompe l’oeil:

- Vanitas Paintings: Dutch still-life painters often used trompe l’oeil techniques in their vanitas paintings. These works featured seemingly real objects like skulls, hourglasses, and wilting flowers, all designed to remind viewers of the transience of life and the impermanence of material wealth.

- Faux Architectural Elements: Trompe l’oeil was frequently used to create the illusion of architectural elements like niches, shelves, and alcoves filled with objects or figures. These elements were so convincing that viewers might believe they were viewing a real niche with sculptures or a hidden alcove with treasures.

- Faux Stone, Marble and Wood: Artists emulated the appearance of different materials, such as marble and wood, with astonishing accuracy. Walls often featured marble columns that seemed so real you might mistake them for actual stone or wooden panels that appeared to be sculpted and adorned with intricate details.

- Hidden Messages and Symbols: Trompe l’oeil was sometimes used to hide secret messages, symbols, or inscriptions within paintings. Viewers would only discover these concealed elements upon closer examination, adding layers of meaning to the artwork.

- Maps and Charts: Maps and navigational charts were occasionally depicted with trompe l’oeil. These paintings, often commissioned by explorers and merchants, not only showcased cartographic skill but also added realistic contours and elevation.

- Illusionistic Frames: Some artists painted realistic wooden frames within the canvas itself, making it appear as though the painting were framed and mounted on a wall. This playful blending of the real and the painted further heightened the illusion.

- Everyday Objects: Artists could use trompe l’oeil to paint everyday objects like books, musical instruments, or game boards in such detail that viewers might be tempted to reach out and touch them.

In 18th century France, the emerging Rococo style embraced trompe l’oeil, incorporating it into interior decoration. The Palace of Versailles is a prime example, where for example François Lemoyne’s ceiling painting, The Apotheosis of Hercules is just one of the amazingly illusionistic ceilings.

Another master muralist of this period was the Venetian, Giambattista Tiepolo whose services were in great demand all over Europe and whose murals still fill us with awe today.

Modern Period (19th Century – Present)

Trompe l’oeil continued to evolve through the 19th and 20th centuries. American trompe l’oeil artist William Harnett gained fame for his meticulous still-life paintings, often including everyday objects like newspapers, pipes, and currency. Harnett’s work not only deceived the eye but also carried subtle messages about society.

Trompe l’oeil in Theatrical Scene painting: A Journey of Illusion and Stagecraft

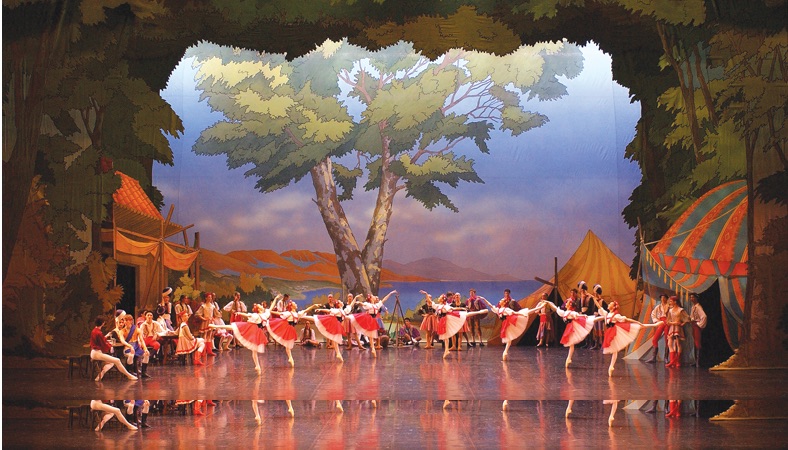

Trompe l’oeil has a rich history in theatrical scene painting, where it plays a crucial role in bringing the world of the stage to life. The use of trompe l’oeil techniques in theatre dates back centuries and has evolved in tandem with developments in stagecraft.

The theactrical origins can also be traced to ancient Greece and Rome. Artists would paint elaborate architectural facades on canvas or wooden panels to create the illusion of grand structures on stage.

The Renaissance and Baroque periods also saw a resurgence of interest in creating illusions on the stage. Design became more ingenious and ornate, with trompe l’oeil playing a pivotal role. Painted backdrops and ingenious props were used to create realistic depictions of landscapes, interiors, and architectural settings. During the 18th and 19th centuries backdrops became even more elaborate.

In the 20th century, while traditional hand-painted backdrops were still used, innovations like cycloramas, large curved canvases that encircle the stage, allowing for dynamic lighting effects fantastical environments.

In contemporary drama, trompe l’oeil techniques are often combined with light shows using computer-generated imagery (CGI). Advanced techniques make the creation of a fantastic setting that leaves very little to the imagination.

The Modern Era

Trompe l’oeil now more commonly known as anamorphic art has found its place in street art. With the advent of social media, artists armed with spray cans, chalk and huge talent, are able to disseminate what are often temporary works. This quality contributes to the dynamic and ever-changing nature of street art, as new pieces emerge to replace old ones.

Anamorphic street art is not static. It invites viewer interaction. Passers-by and media viewers become active participants in the artwork’s narrative as they search the ideal perspective to unlock the illusion. This engagement with the audience adds an element of surprise and delight to the urban landscape.

Artists like Kurt Wenner, Julian Beever and Edgar Muller create jaw-dropping chalk drawings on sidewalks that seem to defy gravity. Sergio Odieth and Peeta take spraycan art to dizzying new heights.

Anamorphic street artists are modern-day illusionists, transforming urban environments into playgrounds of perception. Their works challenge conventional notions of space and reality, reminding us that art can exist beyond the confines of galleries and museums, churches and palaces and that a simple street corner can become a stage for wonder and creativity.

Conclusion

Trompe l’oeil painting has travelled a remarkable path through history, from ancient Greece to our modern streets. Its ability to captivate and deceive continues to intrigue and inspire artists and viewers alike. As each period added its own twist to the art form, trompe l’oeil remains a testament to visual creativity and the enduring fascination with optical illusions.